Project Types

Sustainable Growth Coalition members outline specific practices they’ve implemented in order to add value, improve biodiversity, and engage priority stakeholders. What key questions do you have? Browse this section to learn from others.

- Does the campus have a lot of turf?

- Is there an area that retains a lot of heat in the summertime?

- Is land adjacent to the building limited?

- Are you interested in trees or flowers?

- What about greening your campus roofs?

Native Landscaping

Native landscaping is a simple way to reincorporate native species, such as grasses, flowers, shrubs and trees, into the landscape. Once established, natives are easier to maintain because they are adapted to our particular temperatures and rainfall pattern, resist local pests and disease, reduce soil erosion, build soil structure, and infiltrate rainfall.

Turf Grass

Besides native landscaping, you might also consider low-input turf grass, which provides property owners with benefits including reduced water use, fertilizer, and maintenance expenses. The environmental benefits include more opportunities to reduce run-off. While this is not as robust as conserving or restoring natural habitat, it can be an impactful incremental improvement where habitat restoration is not possible or practical. The University of Minnesota, Turfgrass Science provides resources and assistance to those interested in looking at low-input turf options. For more information, watch this informative video of Sam Bauer sharing information on the low-input turf laboratory on the University of Minnesota campus. Explore turf options with your landscaper and/or facilities management team.

Expectations and Implementations

General Mills

General Mills facilities manager relayed his expectation for prairie—especially as they are working to implement more beyond their current eight acres:

- In one year, if the prairie had been planted in spring with no irrigation, you would be lucky to see six inches of growth, and you will see hardly any flowers

- In two years, the prairie will likely be fairly dull looking and be particularly “weedy” looking to people who do not know what to expect, especially if using flower mixes. Plant growth is likely to be waist high to over six feet tall, depending on the seed mix.

- Maintenance in the first two years is usually fairly easy as General Mills’ prairie vendor comes in to mow it and take down the weeds.

- In the third year and thereafter, spot spraying will take place to try to get rid of different unwanted plants and invasive species.

- Water to help with any trees that are incorporated into the prairie—and to help with maintaining any existing sub-surface sprinkler systems.

To help prevent the spread and takeover by thistle, prairie along pond edges and in parking lots are burned every year, while wood edges and larger prairie sections are burned about every three years. Some flower species, such as Black-Eyed Susan, will germinate in the fall but only 1/8th will survive into the spring. Being careful with seed mixes is important to keep the prairie looking fuller and having decent mixes of flowers throughout the summer. Pay attention to some of the other nearby land uses; turf does better with salt and sand on it than prairie does. General Mills tries to keep prairie eight feet back from sidewalks and parking lot snow drifts, especially if the area does not drain well or if it is flat.

Cost Considerations

Converting from a turf grass lawn to a natural, native landscape does cost more in the first year of implementation, compared to the existing cost to upkeep a turf lawn. However, with five acres or more converted, payback often occurs in as little as two years. With lower maintenance and watering needs, it pays back fairly quickly. Once established, the maintenance costs of natural and prairie plantings can be as low as 1/10th of the cost of maintaining a lawn. Native landscaping with stormwater retention practices like rain gardens, bio-retention areas, and swales can provide more significant monetary benefits such as the reduction or eliminate stormwater fees charged to businesses by municipalities. According to Richard Murphy, Murphy Warehouse is one of the largest businesses “in the city of Minneapolis not to pay a stormwater fee, which would run over $73,000,” due to his stormwater and prairie plantings.

General Mills

While General Mills has not done a full account of the cost differences between turf and prairie, they have not seen much of a difference in cost. The cost is not that different because they only apply 0.9 pounds of fertilizer per acre to their turf in the fall—which is far lower than most turf acres. The turf is mowed more often but is better able to survive salt conditions over winter, so there is not as much maintenance to repair turf in the spring compared to prairie.

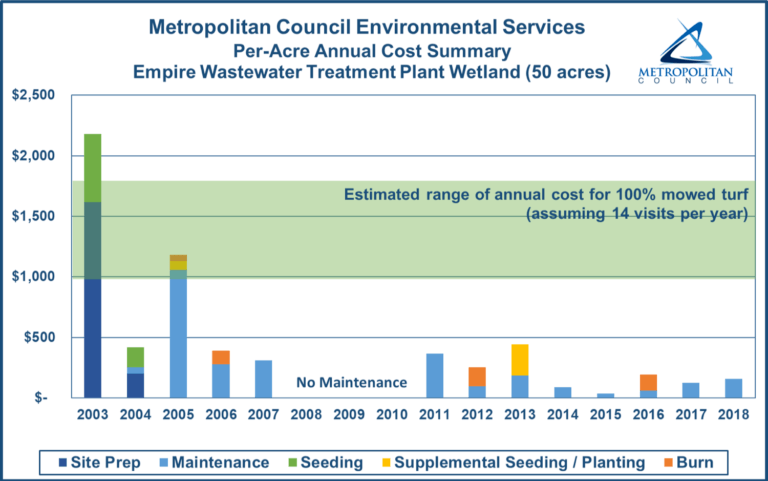

The Metropolitan Council

The Metropolitan Council has found installation of prairies and other native landscapes provide cost savings compared to the typical maintenance of turf landscaping. The Empire Wastewater Treatment Plant infiltration basins are two acres of native vegetation, which were constructed to treat stormwater as part of a wastewater treatment plant expansion. The basins were originally seeded with Minnesota native prairie plants. The Empire Wastewater Treatment Plant wetland is a 50-acre wet meadow wetland that was formerly a wet cornfield. In this project, the Metropolitan Council re-sculpted the site, seeded, and sponsored volunteer planting of shrubs through the nonprofit Friends of the Mississippi River. The estimated, typical cost of mowed turf per acre is approximately $600 to $1,000 per acre per year. These graphs show the cost breakdown for the projects between site preparation, maintenance, seeding, supplemental seeding, and burns. While site preparation and initial maintenance costs are high, costs are usually far under that of typical turf maintenance within a few years.

Urban Canopy

In urban areas, the tree canopy provides an important stormwater management function by intercepting rainfall that would otherwise run off of paved surfaces and be transported into local waters through the storm drainage system, picking up various pollutants along the way. It also works to reduce the urban heat island effect, reduces building heating and cooling costs, reduces air pollution, increases property values, provides wildlife habitat, and provides aesthetic and community benefits.

Expectations and Implementation

Tennant Company

The Tennant Company Foundation donated funds to the Mississippi Park Connection to fund a gravel bed nursery at the Science Museum of Minnesota. The gravel bed nursery required a lot more infrastructure than Tennant’s headquarters had space for, but they saw the importance of providing space for young trees. Tennant Company arranges volunteer events to plant these trees, once they are large enough, along the river in St. Paul.

More information coming soon

- What might the project area require each year?

- What it will look like in year 1 vs. year 3?

- What to anticipate with different kinds of fauna?

- What are things you should be thinking about to make sure this project is successfully implemented?

Cost Considerations

Urban canopy takes a longer time to have a return on investment as trees take a long time to grow. Aside from watering, which is most needed during the first three growing seasons, trees require minimal maintenance. The benefits range from cooling, carbon sequestration, improved air quality, intercepting rainfall, and providing aesthetic benefits. According to a report from the Center for Urban Forest Research, municipal trees in Minneapolis are providing approximately $79 per tree in total net annual benefits and approximate $1.59 in benefits for every $1 spent on tree care. The average annual net benefit is higher for large trees and ranges from $58 to $76.

Green Roofs

Roofs are often overlooked spaces. Roofs can be energy generators with solar photovoltaic panels or solar thermal panels. They can be black or white depending on whether you need them to melt snow, draw solar radiation in the winter, or reflect the hot sun. Or they can be green with the installation of a growing system and plant materials. The benefits of green roofs are reduced heating and cooling costs, increased longevity of the roofing materials, helping to manage urban stormwater, and if accessible they can provide additional green space. The cost-benefit considerations of green roofs are somewhat different than a traditional roof. There may be additional structural support needed, the growing system and plant materials are costs in addition to the traditional roofing system, the first 5 years require more maintenance to establish the plant materials, and there are additional annual maintenance requirements. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency has compiled a list of resources related to the cost-benefit considerations for green roofs.

Expectations and Implementation

General Mills

General Mills has 9,000 square feet of green roofs in Minnesota. Each of the roofs is different and requires its own set of maintenance strategies. One, with shrubs and 20 inches of good soil, has not been watered since 1992. Two new ones implemented in 2011, have soil ranging in depth from 4 inches along the edges to 14 inches in the middle. For these roofs, if it has not rained for a week or so, they are watered.

More information coming soon

- What might the project area require each year?

- What it will look like in year 1 vs. year 3?

- What to anticipate with different kinds of fauna?

- What are things you should be thinking about to make sure this project is successfully implemented?

Cost Considerations

General Mills

For General Mills, the general maintenance cost of 9,000 square feet of green roofs is about $5,000 a year, with the additional cost of fertilizer every other year.

More information coming soon

- What is the general expected ROI from this type of a project?

- What are some of the costs you can expect?

References

Native Landscaping

Bauer, Sam. November 12, 2013. “Living Laboratory- Low Maintenance Turfgrass on Campus.” University of Minnesota.

Bauer, Sam. 2018. “Water-saving strategies for home lawns.” University of Minnesota Extension.

Bauer, Sam and Jonah Reyes. 2018. “Renovating a lawn for quality and sustainability.” University of Minnesota Extension.

Breimhurst, Henry. September 9, 2016. “Most Admired CEOs 2016: Richard Murphy Jr., Murphy Warehouse Co.” Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal.

Green Roof

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. ND. “Using Green Roofs to Reduce Heat Islands.”

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2008. “Green Roofs.” Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies – Draft.

Diboll, Nate. 2008. “Five Steps to Successful Prairie Meadow Establishment.” Prairie Nursery.

Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission. August 2004. “Sourcebook on Natural Landscaping for Local Officials.”

Pizzo Native Plant Nursery. ND. “Native Gardens & Natural Areas: A how to guide.”

Pizzo & Associates, Ltd. ND. “Turf to Prairie: The economical choice.”

Prairie Nursery. ND. “Comparative Life Cycle Costs of No Mow Versus Traditional Lawn Over a 20 Year Period.”

Prairie Restorations, Inc. ND. “Cost Estimates for Prairie Restorations, Inc. Contracting Services.”

Tallgrass Restoration, LLC. ND. “Tallgrass Prairie Facts.”

Turfgrass Science. 2019. “Low-Input Lawns.” University of Minnesota.

Urban Canopy

Center for Urban Forest Research. ND. “The Large Tree Argument: The Case for Large-Stature Trees vs. Small-Stature Trees.”

Chesapeake Bay Trust and Prince George’s County Department of the Environment. ND. “Urban Tree Canopy Fact Sheet.”

deeproot. ND. “Investment vs. Returns for Healthy Urban Trees: Lifecycle Cost Analysis.”

McPherson, E. Gregory., et. al. June 2005. City of Minneapolis, Minnesota Municipal Tree Resource Analysis. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Center for Urban Forest Research, Davis, CA.

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. June 1, 2016. “Cost-benefit considerations for green roofs.”

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. September 2016. “Stormwater Trees.”