Benefits and Business Case

Organizations can save costs, add brand value, and make a difference in their communities and at their companies through creating a more natural habitat in spaces that are currently undervalued. Additionally, companies can capture values that align with their missions.

By installing rain gardens or restoring native prairies, Sustainable Growth Coalition members have seen physical spaces change in ways that reduce maintenance costs, connect with their employees and communities, and improve their environments. Organizations have the opportunity to reap a multitude of benefits by adding circularity to their built environments.

Corporate Trends

Projects that impact landscaping, like pollinator habitat, urban canopy, and green roofs, are trending topics across the state and in the nation. A news search on any of these subjects pulls up new articles every day. Companies are adding brand value and being recognized for the work they are doing, especially around pollinator habitat. As pollinators like bees, butterflies, wasps, and more decline over time and in our region, Minnesotans are understanding just how important they are to our economy and lives.

Additionally, projects focused on preserving, protecting, or reusing water resources on corporate campuses are also gaining momentum. While it is still difficult to measure and directly capture the value of water, Sustainable Growth Coalition members recognize that working on water quality, quantity and access promotes resiliency, supports efficiency and mitigates risk.

Brand Value

Implementation of these projects bolsters corporate image and brand reputation, especially within local communities of focus. Within Minnesota, media outlets are likely to pick up stories about restoring or preserving pollinator habitat and/or water quality. Sustainable campus initiatives are one way to build brand value locally and let the communities you work in know that you care about their neighborhoods.

Andersen Corporation and Xcel Energy

One such example of this was the recognition by local media of Xcel Energy’s partnership with the city of Burnsville to develop and plant pollinator habitat on Xcel Energy transmission line right-of-way within Burnsville park land. Cub Scouts, Girl Scouts, local officials, and others gathered to celebrate the planting during National Pollinator Week.

As of July 2019, Xcel Energy had over 2,100 acres of pollinator habitat in Minnesota, North Dakota and Wisconsin on various company property including under transmission lines, around substations, power plants, community solar gardens, a wind project, and company office sites.

Members of the Sustainable Growth Coalition and peer organizations have seen the local impact of their initiatives. Andersen Corporation and Xcel Energy both signed the Pollinator Pledge, a coalition of organizations formed by the National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Forest Service. The Pledge is committed to improving the populations of pollinators by restoring milkweed and other flowers and plants essential to their survival.

Aveda

Awards and pledges can also help to build a brand’s reputation. Aveda promotes its products as being designed with environmental leadership and responsibility in mind. Showing that they care for the environment beyond just their products, Aveda received the Corporate Conservation Award in 2011 from the National Wildlife Federation for its conservation efforts both on campus and throughout the world.

HealthPartners

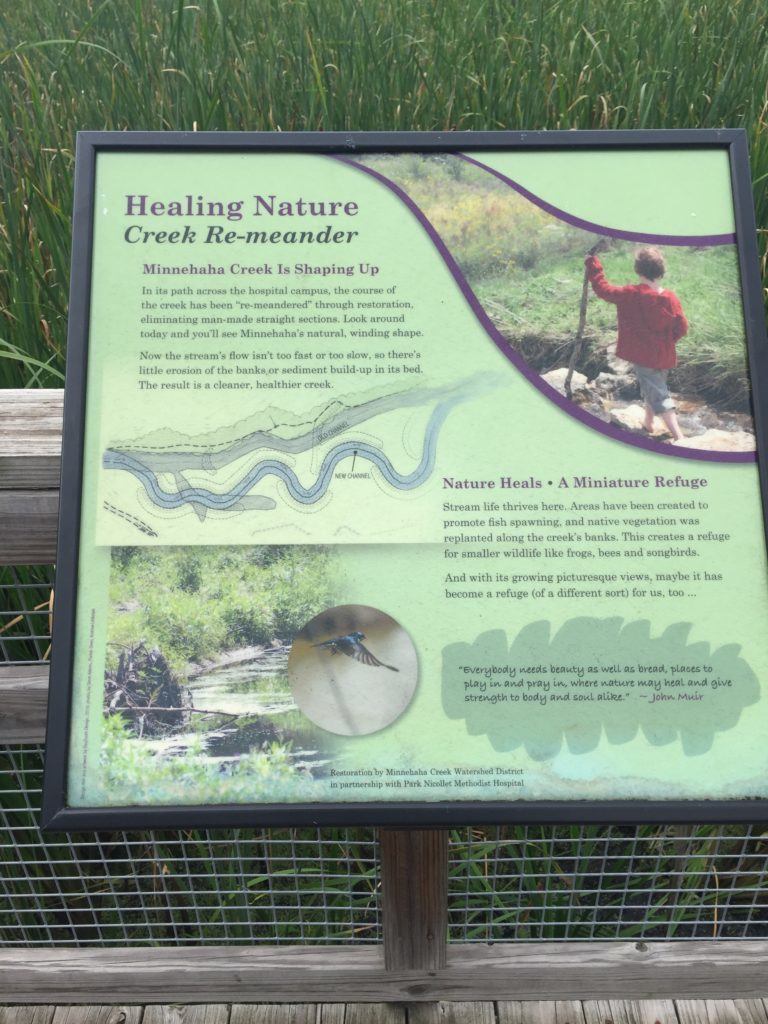

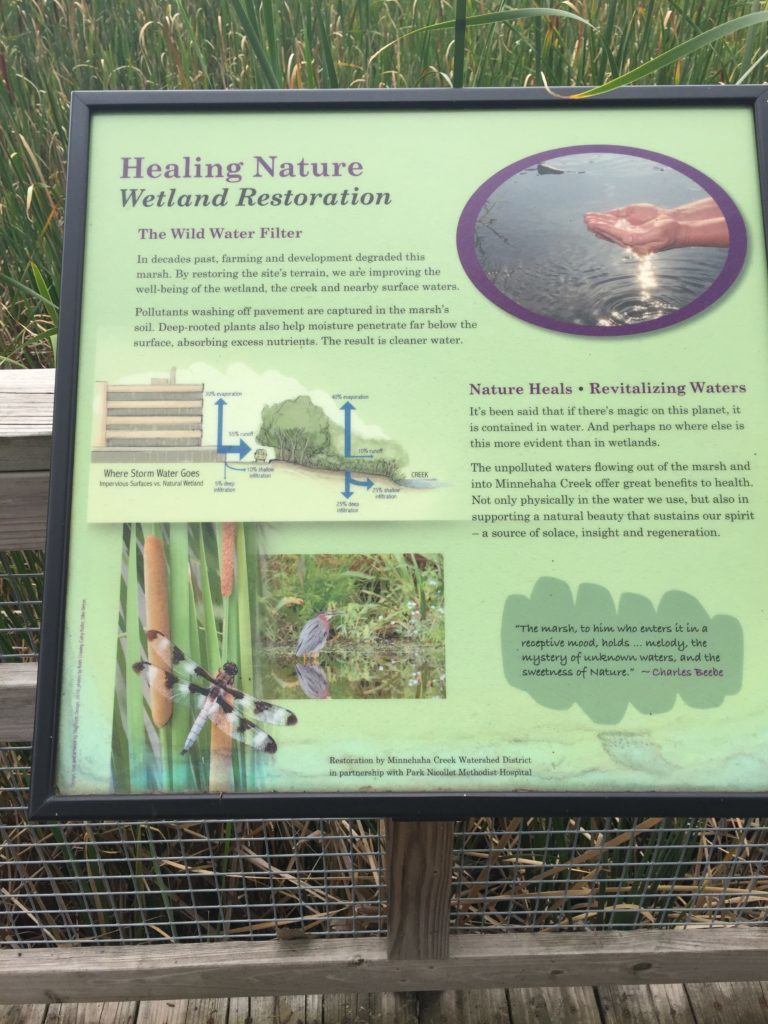

HealthPartners has found national recognition for several of their hospitals due to their outdoor sustainability efforts. The hospital in Amery, Wisconsin has been Certified Sanctuary by Audubon International. Six HealthPartners hospitals have been named some of the greenest in America for their pollinator habitat. HealthPartners Methodist Hospital has been honored by the Minnehaha Creek Watershed District as a Watershed Hero, for their reduced salt use, and for their work in the adjacent riparian wetland and creek bed, which was re-meandered in 2009.

Murphy’s Warehouse

Broader implementation reflects highly on a business’ image, and sometimes on internal leadership as well. Murphy Warehouse’s CEO, Richard Murphy, Jr., has been spotlighted by the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal for his work on sustainability, particularly for the natural green spaces his company has implemented on its campuses. Murphy Warehouse has also won numerous awards for its work on implementing native habitat in its suite of sustainability practices, including awards from the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal, Minnesota Erosion Control Association, Food Logistics, Inbound Logistics, United Sugars, and more.

As you continue to dive into what projects make sense for you, there is a sustainability landscape certification program, through the American Society of Landscape Architects called Sustainable SITES, which is similar to LEED certification, a well-known sustainability building certification program. The ASLA created a slide deck for clients to show the value of certification through the SITES program. This can help you as you build your case for the brand value these projects can provide for you.

Resiliency and Risk

Implementing sustainability projects on your campus can also help maintain or improve property values, promote resiliency, and mitigate risks. For example, the removal of invasive species, like buckthorn, can increase property values, according to several Coalition member facilities. There have also been studies that show that more tree cover enhances property values.

Understanding how facilities relate to water can help plan for the future. A Coalition member mapped their facilities that use the most water along with areas that are water-scarce to better incorporate that into their corporate resiliency plans. By increasing water infiltration, companies can help keep water in the area to help with supply concerns.

General Mills

Another example of resiliency and risk mitigation comes from General Mills World Headquarters in Golden Valley. In the early 2000s, city officials and General Mills executives were dealing with expanding roadway infrastructure while also looking for environmental solutions to increased stormwater from the project. General Mills donated land it purchased in the 1950s and the city developed that land, now called the General Mills Nature Preserve, into floodplain storage and wetlands. This protects the public infrastructure that General Mills employees need to get to work, in addition to providing benefits to the nearby community.

Recognizing the benefits of native vegetation for aquatic water quality and wildlife, the City of Golden Valley also requires native vegetation around ponds for certain linear footage. By requiring this across their city, it helps to create additional sections of habitat that would not necessarily exist otherwise. This ordinance helped provide General Mills’ facilities crew with a push to implement additional rain gardens on their site. Through their rain gardens, retention basins, prairies, and more, General Mills keeps 90-percent of stormwater on-site.

Employee Wellness and Retention

Aveda

At the Aveda campus in Blaine, employees routinely walk the campus grounds for wellness and a chance to get out and enjoy the habitat and see the honey bees. Tours and volunteer opportunities happen throughout the growing season to offer a hand planting native grasses and wildflowers or a lesson in birding. The campus includes natural habitat and water quality features such as rain gardens and pervious pavers, native plantings, honey bee hives and a commitment to sustainable landscaping.

3M

In addition, providing space to talk about landscape improvements can boost employee morale. At 3M’s Cottage Grove facility, an employee group has formed around wildlife and habitat, building connections across employment units. This group helps to organize events to protect the landscape, as well as educational lunch and learns and photo contests on natural beauty.

Community Engagement and Equity

Beyond the benefits to current and future employees such as with retention and recruitment, the community benefits through the environmental improvements that more natural spaces provide. Greater urban tree cover can increase property values even for adjacent properties. Native vegetation projects that incorporate natural stormwater designs can improve water quality and thereby improve recreation activities through cleaner surface waterbodies. The addition of natural spaces—through rain gardens, pollinator habitat, urban canopy, and others—provide tremendous natural aesthetic value that has been shown to improve the lives of those that are in contact with it.

In the urban centers of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Bloomington, temperatures average 2 °F higher in summer than in surrounding areas. That differential can spike as much as 9 °F higher during significant heat waves. Urban heat island effect is stronger at night in the summer and during the day in the winter. In spaces with more paved surfaces and fewer green spaces, the temperatures can rise even more. In poor neighborhoods and areas that are highly industrialized, this is an even greater problem.

By providing a more natural landscape, these differentials can be reduced. The U.S. EPA suggests planting trees and other vegetation as that lowers surface and air temperatures by providing shade and cooling through evapotranspiration, as well as green roofs, which absorb heat and act as insulators, reducing the energy needed to provide cooling and heating, and lowering heat stress associated with heatwaves.

Target

There are other ways to provide community and equity benefits. The Target Northern Campus includes a portion of the Rush Creek Regional Trail system. By connecting to the trail, it opens access to privately held land for public benefit and enjoyment. In addition, Target provides some land to Grace Fellowship Church for community garden space, providing churchgoers who might not have their own land to grow fresh food. Target maintains a garden that grows 2,000 pounds of fresh food a year to use in their corporate dining hall.

3M

At 3M’s Cottage Grove facility, they host community buckthorn and brush removal, bird hikes in the spring, Hastings School comes in to collect seeds, and the Boy Scouts come in to plant trees. There is a rain garden near the site’s offices, giving employees space to sit and enjoy nature.

Environmental Benefits

Water Conservation

When implemented correctly, habitat projects can have significant impact on our water resources. Trees and plants are nature’s stormwater managers, taking up excess water before it flows into storm drains. Native species use this water more efficiently, reducing the need for regular irrigation. Not only do these projects provide a way to manage stormwater while creating lush habitat for pollinators and other animals, they also reduce overall water-related costs in the process.

Water Quality and Infiltration

These natural habitat spaces provide many more environmental benefits than turf grass or parking lots. The root systems of prairie plants, trees, and other native vegetation help to prevent the erosion of soil into waterbodies. Vegetated depressions in the landscape, such as rain gardens, swales, and bioretention areas allow water runoff to be absorbed and reducing the amount of pollution reaching nearby waterbodies, therefore improving the water quality. Trees provide benefits to communities in a number of important ways, beyond water quality.

Temperature and Air Quality

Tree canopy can help cool the temperature of cities and adjacent buildings can experience lower energy needs, especially for cooling in the summer. Trees improve air quality, including pollutants of concern.

Biodiversity

These natural habitat projects provide spaces for biodiversity. Traditional turf lawns are often created to be homogenous, with little habitat for pollinators, and parking lots do not provide any wildlife benefits. Native vegetation, pollinator habitat, and tree and shrub canopy allow for increased mixes of species—both of flora and fauna. These environmental benefits are an important part of showing a more holistic approach to sustainability.

Climate Change Mitigation, Adaptation and Resilience

Native landscaping, urban canopy, and green roofs can help to mitigate climate change. In the case of native landscaping and urban canopy, these methods reduce the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere through reduced maintenance and water use. The deep, dense roots of native plant species sequester carbon in the soil. Green roofs provide climate adaptation benefits by reducing the heating and cooling needs for buildings by providing additional layers of insulation. And native forests and prairies provide climate resilience by reducing the amount of drinking water traditionally used to irrigate turf lawns, allowing that water to be reserved for human consumption.

Employee Education Opportunities

Natural habitat projects can serve as the perfect opportunity to engage employees and the surrounding community in shared learning. Building on the health, wellness, and environmental benefits, these projects provide the opportunity to educate people on the importance of rebuilding our natural capital. Simple things like informative signage, walking tours, living classrooms in the project area, and brown bag discussions provide companies with the opportunity to demonstrate their values in a tangible way while also educating others on the importance of maintaining these spaces.

Signs can benefit corporate employees and visitors alike. HealthPartners has a variety of signs and educational resources at their HealthPartners Methodist site near the Minnehaha Creek (pictured above). General Mills also has signage for their parking lot prairie islands and along sidewalks near prairie to better inform people about their corporate natural habitat practices.

Some organizations take it a step further and also provide examples of how employees can bring their ideas home. For example, 3M’s Cottage Grove provided information through their employee newsletter on how their employees could create rain gardens at home and how to access local resources to do so.

Think about the resources you have and how you can help to spread the message beyond your own borders and help your employees with making changes, too.

Creating Your Internal Pitch

Champions

Who could help you and be a champion for this project?

For example, a well-respected leader within the company or partnering with a brand/department of the company. Think outside the box on this – human resources departments could possibly partner on corporate campus projects as an employee benefit or wellness area, or external communications could benefit by sharing this story more broadly in the community.

Decide who you’re pitching

This could include finance teams, facilities, corporate leaders, brand teams, and more. Make a list of all the departments you need to contact, and what motivates each of them.

How are they influenced (facts and figures, stories, examples of other companies, etc.)? For example, a facilities manager at General Mills suggests bringing them in early to figure out where to place prairie, trees, or even green roofs. They are aware of hard infrastructure, such as sprinkler systems, and soil types that can influence how successful a project can be.

Information to Provide

When making your pitch, decide on the format that best fits your audience (memo, PowerPoint, spreadsheet, etc.). Remember, this is just like a sales pitch – taking time on this step could help move your project forward more efficiently and effectively. Some information that may be helpful to you could include:

- Cost information that informs the bottom line

- Payback timeline

- Maintenance plan

- Cost savings

- Water savings

- Tax implications

- Employee benefit

- Environmental benefit

- Brand reputation

- Any educational materials that could accompany new sits to communicate to guests or employees

- Visual examples of that the project could look like in early lifetime and as it ages

- Support you have received

- Organizational motivations

- Examples from other companies

- Barriers to pursuing a project and maintenance

- Unintended consequences, like long grasses that are too close to walkways. This can hinder plowing in winter and can attract rodents in the summer. Or if controlled burns are required, be sure that smoke will not create issues with building ventilation.

- Decide on a type of project. Please see more information in the Types of Projects section to help you build out your internal pitch.

Public Sector Projects

These types of projects make sense for the public sector as well.

Barr Engineering Company

When the City of Minnetonka decided to create a model landscape for its citizens that demonstrated sustainable landscape design and alternative stormwater management techniques, it hired Barr’s team of landscape architects and ecologists. Barr worked closely with city planners to design a welcoming, user-friendly place that not only serves the needs of people, but also reflects the native landscape of the area. Mowed areas of the campus that were not used as active areas were planted with tough, native plants. Vegetated areas and boulevards capture and treat stormwater by filtering it through plants and soaking it into the ground, preventing it from entering Minnehaha Creek. Barr’s work included:

- Designing a sustainable landscape based on low-input, native plants.

- Creating a primary entry road to improve public safety

- Redeveloping two large parking lots to include stormwater infiltration basins/rainwater gardens and extensive tree plantings to provide shade

- Creating park space in conjunction with an amphitheater and trail system

In 2007, the project was recognized by the City Engineers Association of Minnesota as an outstanding municipal project.

References

Brand Value

Amery Medical Center. November 13, 2017. “Amery Hospital & Clinic Recognized for Environmental Excellence.”

Aveda. ND. “Think Report: Aveda, Employees, and the Blaine Campus.”

Aveda. ND. “Living Aveda: Aveda Cares”

Becker’s Hospital Review. December 3, 2018. “68 of the greenest hospitals in America.”

Breimhurst, Henry. September 9, 2016. “Most Admired CEOs 2016: Richard Murphy Jr., Murphy Warehouse Co.” Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal.

Bui, Tiffany. June 21, 2018. “Xcel Energy land in Burnsville flowers into pollinator habitat.” Pioneer Press.

City of Golden Valley. ND. “General Mills Nature Preserve.”

Giles, Kevin. August 31, 2015. “‘Pollinator Pledge’ kicks off in St. Croix River watershed.”

HealthPartners. December 21, 2018. “HealthPartners hospitals among ‘greenest’ in the country.”

Macie, Ed. April 22, 2016. “Urban Forests: The Benefits Outweigh the Costs.” Land Grant University Extension website.

Mayamek, Telly. October 25, 2017. “When Business and Nature Mix.”

Murphy Warehouse. 2017. “Awards.”

Ogden, Eloise. May 27, 2018. “Helping save pollinators: Xcel Energy creating pollinator habitat by new substation.” Minot Daily News.

Resiliency and Risk

Center for Urban Forest Research. ND. “The Large Tree Argument: The Case for Large-Stature Trees vs. Small-Stature Trees.”

Chesapeake Bay Trust and Prince George’s County Department of the Environment. ND. “Urban Tree Canopy Fact Sheet.”

Macie, Ed. April 22, 2016. “Urban Forests: The Benefits Outweigh the Costs.” Land Grant University Extension website.

Nonko, Emily. May 23, 2018. “What Cities are Doing about the ‘Shocking’ Loss of Urban Forests.” Next City.

Nowak, David J. and Eric J. Greenfield. 2018. Declining urban and community tree cover in the United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 32: 32-55.

Employee Wellness and Retention

American Public Health Association. November 5, 2013. “Improving Health and Wellness through Access to Nature.”

Largo-Wight, Erin et al. 2011. “Healthy Workplaces: The Effects of Nature Contact at Work on Employee Stress and Health.” Public Health Reports 126(Suppl 1): 124–130.

Macie, Ed. April 22, 2016. “Urban Forests: The Benefits Outweigh the Costs.” Land Grant University Extension website.

Seppala, Emma and Johann Berlin. June 26, 2017. “Why You Should Tell Your Team to Take a Break and Go Outside.” Harvard Business Review.

Community Engagement and Equity

Center for Urban Forest Research. ND. “The Large Tree Argument: The Case for Large-Stature Trees vs. Small-Stature Trees.”

Chesapeake Bay Trust and Prince George’s County Department of the Environment. ND. “Urban Tree Canopy Fact Sheet.”

DuBos, Monique. November 18, 2015. “Twin Cities heat island study yields surprises.” University of Minnesota—Institute on the Environment.

Macie, Ed. April 22, 2016. “Urban Forests: The Benefits Outweigh the Costs.” Land Grant University Extension website.

Nonko, Emily. May 23, 2018. “What Cities are Doing about the ‘Shocking’ Loss of Urban Forests.” Next City.

Nowak, David J. and Eric J. Greenfield. 2018. Declining urban and community tree cover in the United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 32: 32-55.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. ND. “Heat Island Cooling Strategies.”

Environmental Benefits

Center for Urban Forest Research. ND. “The Large Tree Argument: The Case for Large-Stature Trees vs. Small-Stature Trees.”

deeproot. ND. “Investment vs. Returns for Healthy Urban Trees: Lifecycle Cost Analysis.”

Macie, Ed. April 22, 2016. “Urban Forests: The Benefits Outweigh the Costs.” Land Grant University Extension website.

Nonko, Emily. May 23, 2018. “What Cities are Doing about the ‘Shocking’ Loss of Urban Forests.” Next City.

Nowak, David J. and Eric J. Greenfield. 2018. Declining urban and community tree cover in the United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 32: 32-55.

Tallgrass Restoration, LLC. ND. “Tallgrass Prairie Facts.”